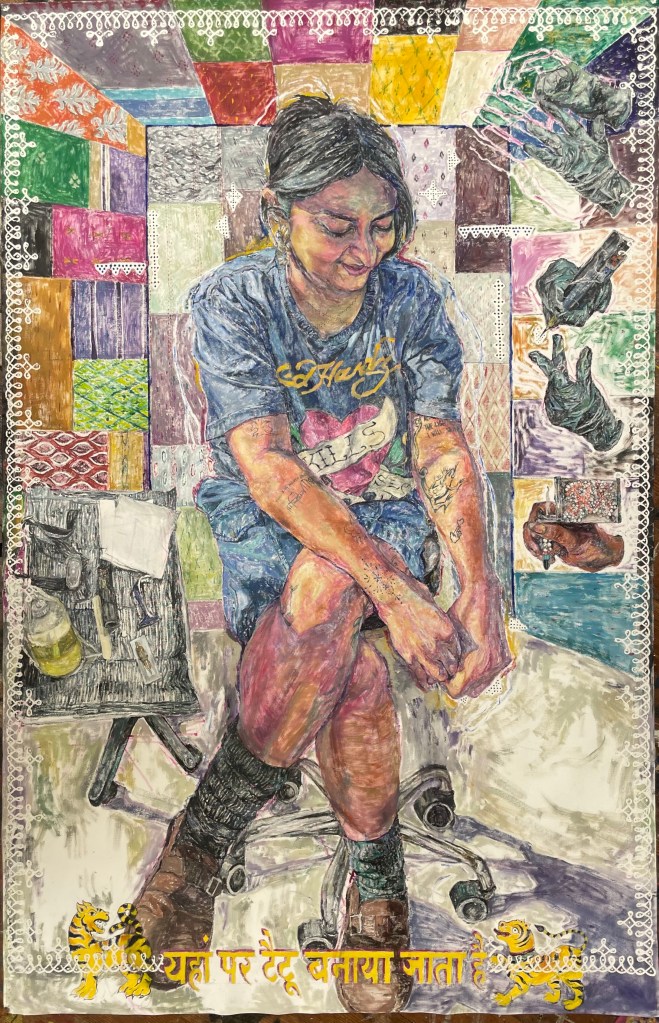

I met Mumbai-based tattoo artist Utsavi Jhaveri (@border.line.tattoos) on an uncharacteristically sunny San Francisco day in February. We sat outside Castro Tattoo, the studio where she was guesting on the SF-leg of a US tour. Dressed in the perfect tattoo artist uniform, she wore baggy jorts and an oversized t-shirt printed with the iconic Ed Hardy “Love Kills Slowly” heart and skull. Her outfit revealed an impressive collection of tattoos, the most stunning of which was a Trajva composition around her neck and collarbones. Trajva, a Gujarati tattoo tradition, is often characterized by jewelry-like dot- or line-work compositions. I had been following Utsavi on Instagram for months and was obsessed with the way she drew inspiration from tattooing traditions across the subcontinent, alongside textile work, bindi patterns, and the work of other young South Asian contemporary artists. We finally met up, not for an actual tattoo appointment, but because I had purchased one of her mini zines. Alongside her own personal account, Utsavi runs @indiastreettattoos, an account where she documents “the subculture of street tattooing in India.” She describes the account as “an exploration of the caste and class divide that very much exists in [India]. There is such beauty in these artists’ work, often ignored… due to lowered hygiene standards practiced by them.” In her zine “Gali ki Sher” (transl. Lions of the Streets) she documents designs and scenes from the tattoo artists she spends time getting to know, using her own money as well as proceeds from her sales to pay the artists she documents.

In my own painting practice, I’ve been obsessed with art that’s often excluded from the “fine art” spaces — movie posters, sports photography, album covers, and, of course, tattooing. As someone born and raised in multicultural American communities, I feel such a prominent yet unnatural separation between what we label “fine art” from the art we consume every day — the art that shapes our interests, thoughts, friendships, and the spaces that attract us. During my recent trip to India, a few weeks after hanging out with Utsavi, I came prepared with gifts — little prints I’d made of a few of my paintings. On giving some to an old family friend, I saw this uncle seem to shy away. He said something along the lines of “Oh, I don’t know what this is about. I don’t really know anything about art.” I can see these sentiments echoed in the eyes of so many family members and friends that feel like they don’t want to say the wrong thing about my work. But at the same time, I see these same loved ones in their homes adorned floor to ceiling with religious art and decoration. Their closets are filled with clothes whose names and traditions they can pinpoint. Every one of my elder female relatives will tell me about chikankari and kalamkari and block printed textiles, about which sarees are from which region and made with which material; my friends similarly express such strong tastes in music, fashion, and tattoo styles. It’s strange to see people who undeniably have developed tastes think that they’re not qualified to speak on certain kinds of art. We forget that art isn’t just for artists, at least it shouldn’t be.

During my research on South Asian tattooing, I find myself coming across this persistent narrative that tattooing, until very recently, had faded almost entirely from mass Indian culture. And this narrative persists because it’s mostly true. Tl;dr It’s the tried and true story that in the wake of British colonialism and missionary-imposed values, traditional tattooing was branded as “primitive” and grotesque. In “The Skin and the Ink: Tracing the Boundaries of Tattoo Art in India”, Ambedkar University Delhi researcher Dr. Sarah Haq describes how early colonial writers described tattooing with language along the lines of “hideous” and “a horrible custom.” She discusses how notions of “hygiene” and “cleanliness” around clothing and tattooing are linked with ideas of control over the colonized body. (Important to note that Utsavi, in her tattooing documentation, never comments on street tattoo artists’ methods unless explicitly asked about her own hygiene measures). Even in modern India, these same concepts of “cleanliness” are associated with ideas of education, power, and class, and traditional tattooing is mostly prevalent in rural areas that were less impacted by colonial rule. But at the same time, I can’t help but feel that most of the motifs and traditions of South Asian tattooing tradition feel so familiar despite my lack of experience with any traditional tattoos. Trajva compositions on womens’ arms, legs, and necks make me realize that tattoos are jewelry.

I’m reminded of necklaces I’ve always seen as permanent fixtures on my grandmas and aunts. I remember my own Durga pendant that I’ve worn 24/7 since my mother gave it to me. I learn about the tattoos that Baiga women traditionally get at or after marriage — the dots on their toes and designs on their foreheads — and think of the toe rings and kumkum I see married women wear today. I read about tattoos that Baiga and Mer women get after marriage and think of the mangalsutra my mom wears only when we’re in India around older relatives, the same way I hid my first tattoos from her for years.

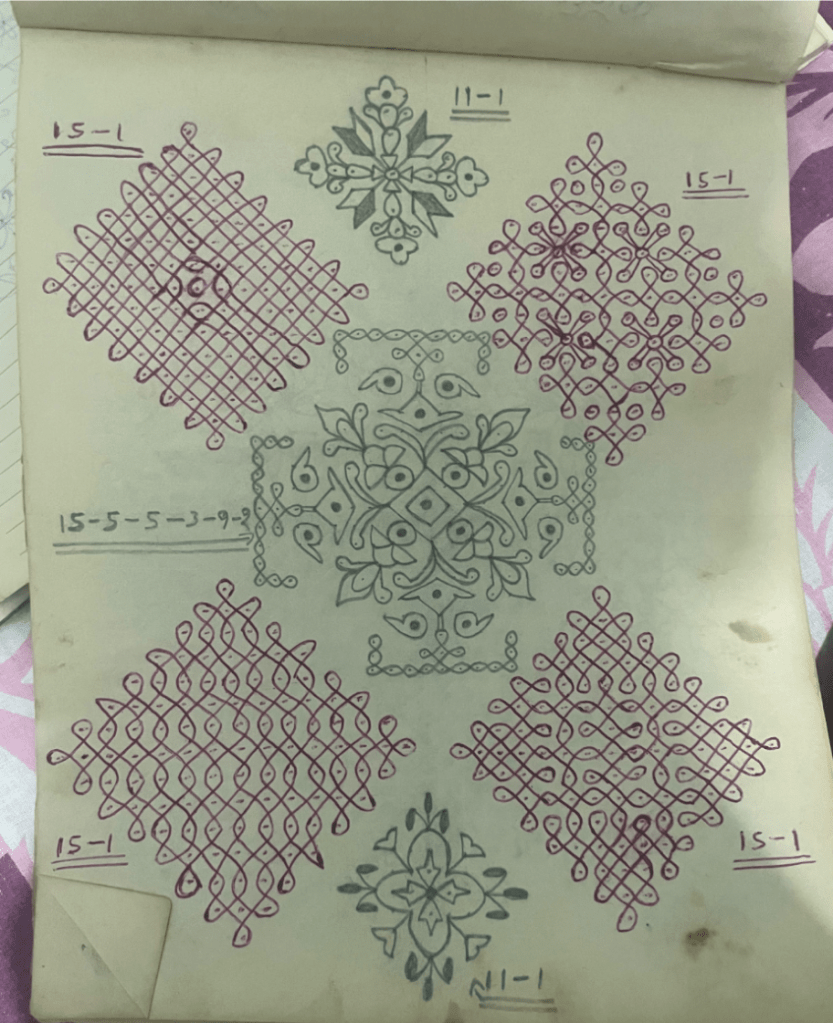

The muggu/kolam designs I see on the front porch of my family home in California, on almost every potted plant and doorway in Warangal, are the same ones I learn about in articles on traditional South Indian tattoos.

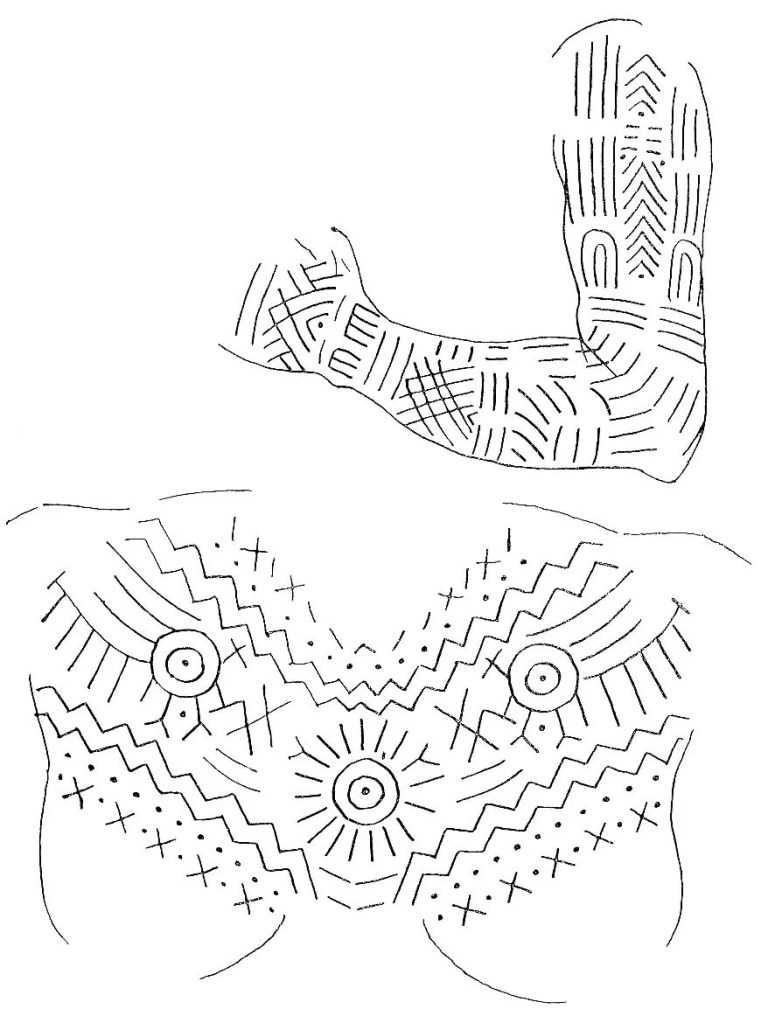

Photo of Bhumia body tattoos, courtesy of Lars Krutak

I actually got my own teensy muggu tattoo before I had even done any of this research on tattooing — I just always loved them on our doorway, I had no idea they were part of their own rich tattooing tradition.

Utsavi’s practice and documentation work remind me that the ethos of tattooing culture has always stayed relevant in South Asian cultures. The desire to hold stories, histories, and personal connections on our bodies was, is, and always will be a part of our cultures. The work she, along with other India-based tattoo artists, does redefines these ideas around body and power. These conversations feel so relevant to the conversation around contemporary artists from underrepresented backgrounds often turning towards figurative art. Right now, I can speak to a huge surge in Asian American figurative art, adding much needed nuance to how we see ourselves and our communities in the Western world. Tattoo artists aren’t alone in emphasizing the importance of the interaction between the artist and the human body — both their own and their subjects’.

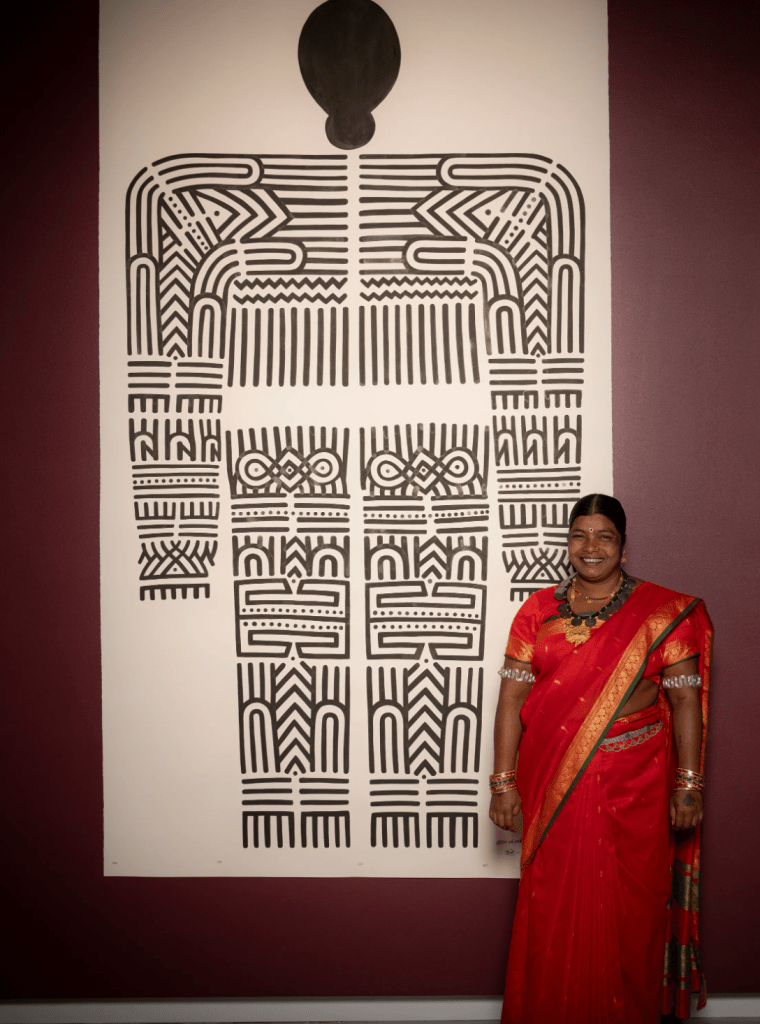

In the BBC Radio podcast Mortal Work of Art, Dr. Matt Lodder discusses the way he uses an art historical framework to research American, European, and Japanese tattooing . He describes how most research in tattooing is anthropological, ethnographic, or criminological — it views tattoos entirely through the “tattooee” and removes the tattooer from the research entirely. We fail to understand who the important tattoo artists of time periods and cultures were, how their designs changed, and why certain tattoos come in and out of fashion. Tattooing isn’t just about particular histories — it’s also about design, human interest, and trend. The new research around tattooing that academics like Lodder and Haq are doing reflects a framework that inspires me in my work around tattoo artists, music, and sport. These notions of collaboration and dual ownership are essential to the way they view and write about tattooing, giving autonomy back to the tattoo artist and understanding them as an artist. Tattoo artists like Mo Naga and Mangala Bai Maravi, from Nagaland and Madhya Pradesh respectively, are revitalizing and documenting their cultures’ tattooing traditions as independent artists who create their own evolving and inspired work. Mo Naga started his career as a fashion student, but learned about Naga tattooing traditions in 2007 while researching indigenous textiles.

He left fashion to begin a rigorous project of research and documentation of Naga tattooing that eventually gave birth to his own practice. He tattoos non-Nagas with designs drawn from non-tattoo Naga motifs and reserves tattooing imagery, with its specific meanings and significance, for Naga tattooees. Mangala Bai Maravi is the daughter of Baiga tattoo artists, and learned the art of tattooing by the age of seven. Following in her mother’s footsteps, Mangala Bai shows large-scale canvas paintings of tattoo designs in museums and cultural institutions around the world, currently completing a residency at the University of Sydney.

My painting of Utsavi is inspired by our conversations, this research, and a desire to learn from Mangala Bai, Mo Naga, Dr. Lodder, Dr. Haq, and countless others. As a figurative artist, I always incorporate my subjects’ stories, personalities, and own work in my pieces. I want to give my work as much of a collaborative energy, like tattooing, as I possibly can. In developing my series on tattoos, I intend to continue my own reading but also learn from the research and practices of contemporary South Asian tattoo artists who are drawing from their own histories and artistic inspirations. In March, during my time in Bangalore, I got to know Triparna Mishra (@bananatatz), another incredible tattoo artist drawing from Pattachitra traditions and her own work as a fine artist in a family of fine artists. My painting of Triparna is TBD, but in the meantime, I want to write about my work and temporarily shift away from portraiture to focus on the designs themselves. The past few years in the art world have taught me so much and have given me so many incredible experiences but have also made me realize that the gallery/museum/institutional art world is fucked. I feel like we all know this. But the art world’s disappointing yet unsurprising reactions to the ongoing genocide of Palestinians have made so many of us emerging artists question what we define as success, who we want to be able to see our art, and what we actually see for ourselves in the future. This research is partially a way for me to think about those questions. Dr. Lodder states, “I was asked this question the other day: ‘Does tattooing need to be in a fine art gallery to be validated? And my answer is no… it’s got its own validation on the skins of people worldwide,” on the bodies of the people who truly care for and hold the art.

References

https://www.afar.com/magazine/tattoo-artist-mo-naga-keeps-naga-tattoo-traditions-alive

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b039pdtg

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-86566-5_2

Leave a comment